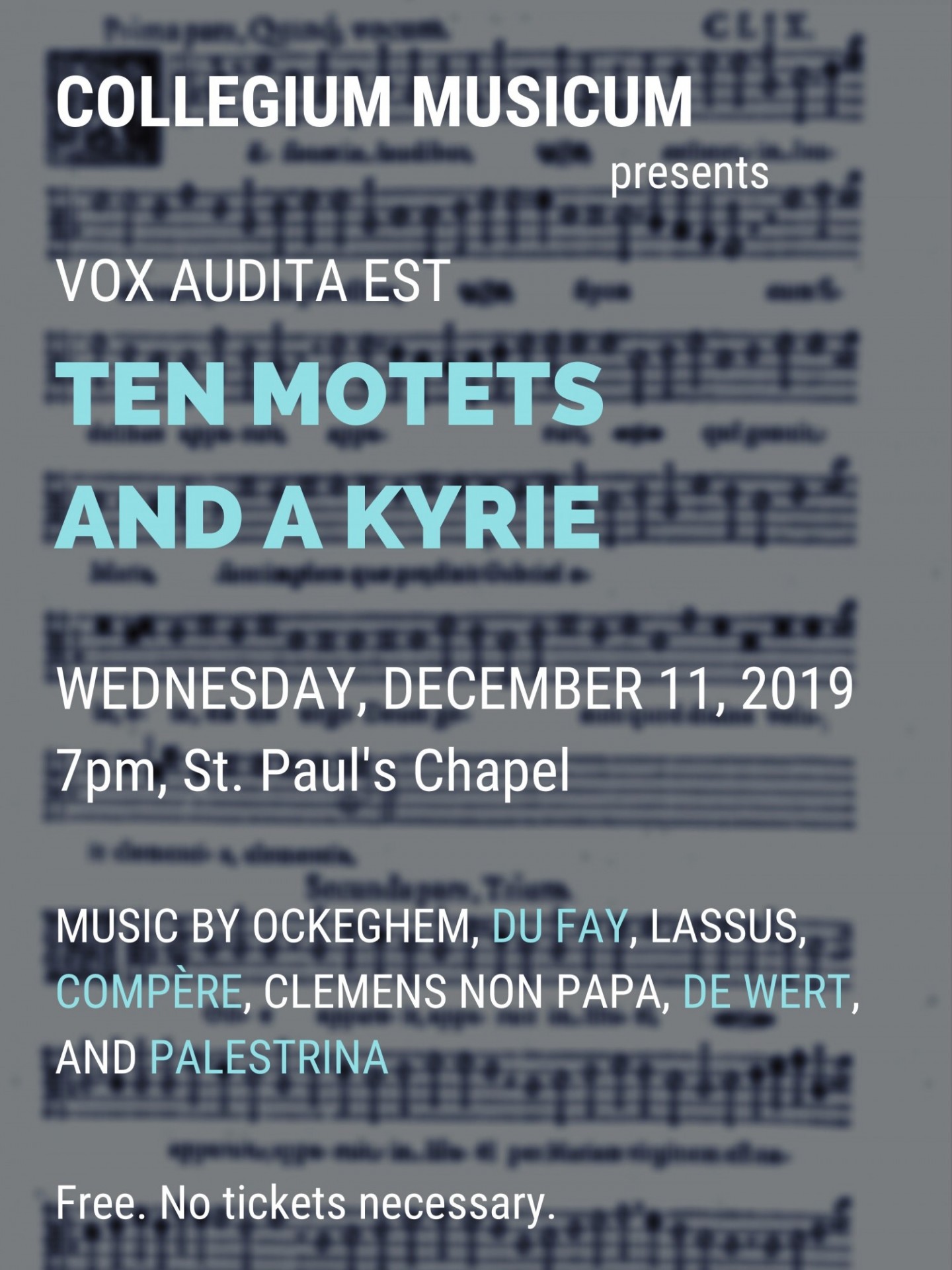

Vox Audita Est: Ten Motets and a Kyrie

Collegium Musicum, Columbia University's early music chamber choir, is pleased to present its Fall 2019 concert, "Vox Audita Est: Ten Motets and a Kyrie," to take place in St. Paul's Chapel on Columbia's campus Wednesday, December 11th, at 7pm.

The concert will feature motets (and one Kyrie) by Johannes Ockeghem, Clemens non Papa, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Loyset Compère, Giaches de Wert, and Orlande de Lassus.

The concert is free and open to the public. No tickets necessary.

Music Director, Russell O'Rourke

Program

- Alma redemptoris mater - Guillaume Du Fay

- Sicut cervus - Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

- Sitivit anima mea - Palestrina

- Beatus vir - Orlande de Lassus

- Margeaux Wolberg, soprano

- Anna Apostolidis, alto

- Vox in Rama - Giaches de Wert

- Duo No. 15 (from the Cantiones duum vocum) - Lassus

- Eduardo Cordero, flute

- Sonja Wermager, violin

- Kyrie from the Missa Prolationum - Johannes Ockeghem

- Virgo caelesti - Loyset Compère

- Oculus non vidit - Lassus

- Isabella Livorni, soprano

- Katharine Halls, alto

- Ego flos campi - Jacobus Clemens non Papa

- Sancti mei - Lassus

- Wiebe Copman, tenor

- Justin Gregg, bass

- Resonet in laudibus (prima pars)

- Hodie apparuit (seconda pars)

- Srinidhi Bharadwaj, alto

- Grant Woods, tenor

- David Newtown, bass

- Magnum nomen domini (tertia pars) - Lassus

Ensemble

Soprano

Anna Apostolidis

Katharine Halls

Isabella Livorni

Nancy Mandel

Audrey Nicholson

Margeaux Wolberg

Alto

Srinidhi Bharadwaj

Kaiyi Chang

Rae Fan

Ursula Murray-Bozeman

Emily Rutherford

Sonja Wermager

Tenor

Callum Blackmore

Eduardo Cordero

Cheng Wei Lim

Richard Neuberg

Grant Woods

Yichu Xu

Bass

Wiebe Copman

Justin Gregg

Warren McCombs

David Newtown

Vinzent Wesselman

Program Notes

All the pieces on tonight’s program set sacred Christian texts, all are polyphonic (meaning that they feature multiple simultaneous, overlapping melodies), all were written during the period of Western music history we call the Renaissance, and all but two are in Latin. From there on, they differ.

In Guillaume Du Fay’s (1397–1474) Alma redemptoris mater, from the mid-fifteenth century, the highest of three voice parts paraphrases a plainchant antiphon in praise of the Virgin Mary, while the lower two voices twist and turn below (and sometimes above) it. For the majority of the piece, only this highest part carries the text, while the other two chant a single vowel—a first, then i—on longer notes, cradling the sacred words in a halo of harmony. In a remarkable middle section starting at the words Tu quae (You who), however, all three parts take up the text, and the rhythmic activity thickens into a hushed patter: listen for the call-and-response at tuum sanctum genitorem (your holy begetter), shortly after which the spotlight returns, for the remainder, to the upper voice.

If Collegium were stranded on a deserted island with only one piece of music to sing, I think many of us would pick Palestrina’s (1525–1594) Sicut cervus. So beloved that it has its own Wikipedia page, this classic motet setting of two verses from Psalm 42 earns its place in the Renaissance pantheon through its yearning melodies, which give expression to the spiritual urgency of the text, and its carefully-paced build to the climax at ad te Deus. Just before the end of the motet (you’ll know when it’s coming), listen for the rapid entrances of bass, alto, and tenor on these words, which urge the piece on to its conclusion (-us). Sicut cervus is followed without pause by its lesser-known but no-less-worthy partner Sitivit anima mea.

Threaded throughout the remainder of this program are four duos by Orlande de Lassus (1532–1594): Beatus vir, the instrumental Duo No. 15, Oculus non vidit, and Sancti mei, all first published in Lassus’ Cantiones duum vocum of 1577. Tonight performed by soloists, these pieces are brief but dense, exhibiting a variety of contrapuntal techniques characteristic of sixteenth-century polyphony including imitation (where one voice copies another), inversion (where a stretch of music is flipped such that the low melody becomes the high one, and vice versa), and retrograde (where a melody is heard twice, but the second time backwards). But these are not necessarily features to grasp on a first listen; what will be clear, I think, is the balanced exchange between the two parts as they traverse sinuous melodic paths.

After Beatus vir is Giaches de Wert’s (1535–1596) Vox in Rama. A setting of Matthew 2:18, which relates a portion of the Massacre of the Innocents (in this verse, Herod the Great’s execution of Bethlehem youths is foretold through an Old Testament quotation), this five-voice motet is our evening’s high point of pathos. More than that, it is an object lesson in techniques of musical anguish. Chief among them is Wert’s expressive use of the semitone, the smallest melodic interval available to him, and a dissonance when heard simultaneously between two parts. Listen for this interval at the very beginning of the motet between the words Vox and in (a warped echo of the warm whole tone ascent that begins Sicut cervus); listen for it again at Rachel plorans (Rachel is weeping), whose melody moves by semitone along a dramatic descent, lament made audible; and listen for it a third time in the long closing section on et noluit consolari quia non sunt (and she will not be comforted because they are no more), where this interval’s participation in the contrapuntal fabric catalyzes some startling chord changes.

With the instrumental Duo No. 15 concluded (see above), we offer two late fifteenth-century studies in rhythmic complexity. First is Johannes Ockeghem’s (d. 1497) Kyrie from the Missa Prolationum, a piece famous for its contrapuntal and notational ingenuity. Although four parts sound, only two were written down by the composer, a feat made possible by the alchemical transformations afforded by Renaissance mensural notation (these transformations are alluded to in the title’s technical term prolationum. In short, Ockeghem derives the alto and bass for his Mass movement from the notated soprano and tenor, respectively, resulting in what we call a double canon. But there is more: while the alto copies the melody of the soprano, and the bass the melody of the tenor, they do so—in the opening and closing sections of this three-part work—more slowly than their faster-moving models. The result is bewildering to wrap your head around but inviting to hear. My recommendation is to kick back and enjoy it; if you hear echoes of one part in another, then all the better.

Loyset Compère’s (1445–1518) Virgo caelesti uses rhythmic complexity to a different effect. Although you will see me conducting a triple meter, this short, five-voice motet often obscures that organizing principle through syncopation and displacement. Where the middle of five voice parts introduces the first melodic theme on beat one of the measure, for example, the sopranos shortly thereafter sing the same melody, but starting on beat two. The result is music that floats, each voice part seemingly disinterested in the others but together spinning something rare and delicate. The floating effect is also thanks to Compère’s rather loose approach to his text, a hymn to the Virgin Mary whose source remains unknown: instead of matching the natural accents of the Latin through parallel musical accentuation—as, for example, Palestrina and Wert are careful to do—Compère lets his melodies stretch their syllables beyond audible recognition.

Our penultimate motet is Jacobus Clemens non Papa’s (c. 1510–1555) Ego flos campi, a setting of Song of Songs 2:1–2 and 4:15. This section of the Old Testament celebrates sexual desire and earthly love, subject matter the composer matches with lush, unending consonance. With seven individual voice parts, this is indeed our densest motet. Yet balancing that density are Clemens’ clarion, text-driven rhythms—you won’t find obfuscation of the meter here—and his careful control of the performing forces. Although most of the motet proceeds in imitative polyphony, with each of the seven parts ducking in and out of the others, a striking moment of unison stands at its center: at the line Sicut lilium inter spinas (As the lily among thorns), the choir gathers for extended passage of homophonic declamation, singing the line thrice. The effect is not dissimilar to boldface font on a printed page, and scholars have pointed to a likely symbolism for the device: Sicut lilium inter spinas was the motto of a lay devotional organization, the Marian Brotherhood at ’s-Hertogenbosch, to which Clemens dedicated a motet in 1550. Collegium member Justin Gregg has called Ego flos campi the “greatest piece of music ever written.”

Lassus’ Resonet in laudibus, in three parts, closes the evening. The theme of the text is Christ’s birth, and you will hear the spirit of the associated holiday in Lassus’ buoyant polyphony. While rhythmically intricate, with little offbeat motifs bouncing around the choir for its duration, this motet has, by contrast, straightforward harmony, rarely straying far from the tonic. Responding to this quality, Collegium member Nancy Mandel has called the motet a “one-chord wonder” (a critical category, so she tells me, derived from the American shape-note tradition). Most wondrous of all is the composer’s setting of the word Eya, a celebratory cry that needs no translation. At this word, the choir toggles back and forth between two chords repeatedly, but with each of the five voice parts displaced in time from its neighbor such that a cacophony of offset E’s and ya’s results.

A middle section, Hodie apparuit, similar in character to the first one but reduced in texture to three voice parts, will be performed by soloists, followed by the return of the full choir for Magnum nomen Domini. This last section introduces some new material (including my favorite note on the whole program, an unexpected minor-making E-flat in the tenors a few bars in), but can’t seem to resist the pull of Eya: the motet concludes with a recap of this joyful chorus. --Russell O'Rourke